The final installment of this eight-part series[1] will be about the last days of Huseyn Ali bey and the embassy team in Europe and Oruj bey Bayat’s famous conversion to Christianity and his taking the name “Don Juan.”

In Spain

I noted that the embassy entered the city of Valladolid on 13 August 1601. According to the report of Domenico Ginnasi, the nuncio of the Vatican in Spain, dated 19 August, Huseyn Ali bey was in contact with other diplomatic representatives in the palace of King Philip III. Huseyn Ali even had a small argument with the French ambassador to Spain, Antoine de Silly,[2] because he thought that France was not Catholic, but Protestant.[3] At this time, relations between Spain and France were at a low point: France was supporting the rebels in the Netherlands against Spain and maintaining good relations with the Ottomans. On 18 July 1601, the Spanish government raided the embassy building and arrested several of the ambassador’s employees. On the same day that Huseyn Ali bey was admitted to the Spanish court, King Henry recalled the ambassador to France.[4] Later, other diplomats in the Valladolid court explained to Huseyn Ali bey that King Henry was no longer a Protestant.

According to Oruj bey’s writings, the Duke of Lerma[5] visited Huseyn Ali bey 4 days later.[6] On 30 August 1601, the advisers and ministers of King Philip III—the Cardinal de Guevara,[7] the Count of Chinchon,[8] the Constable of Castile,[9] the Chairman of the Council of Orders[10] the Duke of Alba,[11] the Count of Miranda and the priest Gaspar de Córdoba, the chief confessor of the king—began to discuss the letter sent by Shah Abbas to the king. After the letter, the memorial submitted by Huseyn Ali bey to the palace was also considered. In his application, the ambassador said that he was waiting for a reply from the King of Spain to take to Shah Abbas, and that the governor in Hormuz should give free passage to the Safavid merchants. Another issue mentioned at the end of the letter was about the pieces of iron brought by Portuguese merchants to the markets of Hormuz. According to Huseyn Ali’s memorial, these pieces used to make swords were too short and the industry needed to lengthen them was not available in his country, so he asked that those pieces to be lengthened by four fingers. In addition to all this, the ambassador stated that his financial resources have already run out and that he desired to return to his country soon.

After much deliberation, the royal council gave Philip III the following advice:

- Since Shah Abbas is a neighbor of Hormuz and an enemy of the Turks, Spain should show a warm attitude to the Shah. Considering that the Safavid queen is a Christian, ambassadors should be a religious people.

- The Catalan canon should prevent Huseyn Ali bey from going to France and Venice and accompany him to Portugal.

- Unlike the Holy Roman Emperor and the Pope, the King should allocate more money than anyone else to show off his wealth, and grant 10.000 ducats to Huseyn Ali bey. Two thousand ducats from this should be paid on the way to Lisbon, and the remaining 8.000 should be given for the rest of the journey. In addition, the royal council advised to give the ambassador a portrait of Philip III and a gold chain, a sword with a golden scabbard or a precious stone, and to find a good ship in Lisbon.

- The ambassador’s other wishes were left to the Viceroy in Portugal.[12]

The council then met again on 7 September. In this meeting, the increase of the money to be given to Huseyn Ali bey (to 30.000 ducats) and the division of the Ottoman lands between Spain and the Safavid state were discussed. Although the proposal for the division of Ottoman lands was viewed positively, the council also recognized that this proposal was far from reality. The council recommended the Portuguese captain Antonio de Escobar as ambassador, and concluded that it would be appropriate to have a Castilian Jesuit priest accompany him. Long before the meeting, on 27 August 1601, the Duke of Lerma wrote to Pedro Álvarez Pereira, secretary of the Portuguese Council. He asked the latter to instruct Antonio de Escobar to speed up his work in command and praised his exploits in Flanders and France.[13] According to Carlos Alonso, this already showed that he had been considered for such a task for a long time.[14]

Three days later, on 10 September 1601, and on 20 September, the Duke of Lerma wrote to Pereira again, instructing him to allocate funds and start preparations for Huseyn Ali bey’s arrival in Portugal. According to King Philip III’s order, Huseyn Ali bey was to receive 2.000 ducats for shopping, 1.000 ducats for going to Lisbon, and 8.000 ducats from the Portuguese viceroy for his time in Lisbon.

The songs of the Safavid ambassadors

While the Safavid ambassadors were in the Valladolid palace, the queen Margaret of Austria,[15] gave birth to her first child, Anna, on 22 September. The Safavid ambassador Huseyn Ali bey had to postpone his trip to Portugal. The baptism of the new princess was solemnized on 7 October at the San Pablo Cathedral in Valladolid. According to the writings of the Spanish court historian Luiz Cabrera de Córdoba, Huseyn Ali bey also participated in this ceremony:

The Persian ambassador was in a gallery, in a corner of the main chapel, observing what was happening from there; and he seemed very pleased with it.[16]

Although not recorded in Spanish archives, Girolamo de Sommaia,[17] a Florentine researcher who lived in Spain at the time and studied at the University of Salamanca, recorded that Huseyn Ali bey sang a song during this ceremony. In his manuscript coded CL VII 353,[18] stored in the National Library of Florence, Sommaia, he attributes two songs to Huseyn Ali bey and Oruj bey Bayat respectively. He names Huseyn Ali bey’s song as “Canción que el Embaxador de Persia hizo al nacimiento de la Princesa” (Song that the Ambassador of Persia made at the birth of the Princess).[19] Francesco de Benedictis, who studied both of these songs, believes that the author of the lyrics was actually Oruj bey Bayat who had learned Spanish. Francesco attributes this to Oruj bey’s high-quality education in Iran.[20] In one of the last articles he wrote before his death, Luiz Gil Fernandez, who deeply studied the relations between Spain and the Safavids, pointed out that it was naive to believe that Oruj bey would be able to write a sonnet or a rhyming poem in the Castilian language in a short period of time.[21] Although the question of Oruj bey’s authorship is in doubt, de Peiresc, a musical researcher of the time,[22] testifies to Huseyn Ali bey’s music knowledge. In a letter written on 13-15 October 1633, de Peiresc told his friend Marenne Mersenne that:[23]

…and I myself saw the Persian ambassador in 1601 when he came to see Pope Clement in Rome. He played the guitar with enthusiasm and very well.[24]

It is necessary to clarify “guitar” here. We are probably talking about a lute, which is similar to the “oud” instrument that was familiar to the Safavids. In my opinion, Huseyn Ali bey performed the song in Rome and Valladolid, and Sommaia later presented it in the style of oriental exotica—perhaps with the help of Oruj bey – by writing a poem in Spanish on their behalf. Pietro de’ Medici from Florence (brother of Duke Ferdinando of Tuscany) was also present at the baptism.[25] Given the close friendship between Sommaia and Orazio della Rena, the secretary of the Tuscan embassy in Spain, it is possible that he heard the information about the performance of these songs from representatives of the Tuscan embassy.[26]

Conversion of Aligulu bey Bayat

According to Oruj bey, the embassy stayed in Valladolid for 2 months. When the members of the Safavid embassy rode around the city as a leisure activity, they were widely discussed by the women around them.[27] However, among the members of the embassy there was one person who was missing: Aligulu bey Bayat. According to Oruj bey’s writings, Aligulu bey disappeared for a while. According to the report sent to the Vatican by canon Guash, who brought the embassy to Spain, Aligulu bey was ill for 3-4 days:

The Persian ambassador will be dispatched very soon, and his nephew has converted to the Catholic faith and has been away from our palace for many days, although he is ill. It is understood that the king will be his godfather, or “santolo,” and the queen his godmother, or “santola,” when he is baptized. Yesterday, while I was at the house of the said Persian, the king sent him a very rich outfit, made especially of black velvet with silver lace, a doublet of brocade, a hat from the same king with white feathers, and a very curious gilded sword and dagger, also from the king. Indeed, the king will certainly provide him with very good food. The Persian ambassador has shown me a displeased and unfriendly face for some days, saying that I persuaded him [Aligulu bey] to become a Christian. But I consider it all well worth the effort. […][28]

In Portugal

Although Oruj bey Bayat did not note when the embassy left Valladolid, we learn from the Spanish archives and the report of nuncio Ginnasi that the royal family went on a hunting trip to the Castrocalbon forest 2 days after the baptism of the princess. In the report from 16 October 1601 written by the nuncio about the departure of Huseyn Ali bey, we read such an interesting note: “It is said that he took two Spanish women with him. If so, I don’t know how it was allowed.”[29]

He left for Portugal with Diego de Urrea, the translator assigned to them, and first arrived in the city of Segovia.[30] The embassy spent two days in the city visiting places such as the Sanctuary of the Virgin of La Fuencisla,[31] the Alcazar of Segovia,[32] the Roman aqueduct, and the Segovia Mint.[33] Although local historian Diego de Colmenares from Segovia wrote about this visit of the embassy, it is interesting that he takes all his information from Oruj bey’s book and gives the date of their entry into the city as 14 October, but presents the embassy as if it was sent by Muhammad Khudabanda.[34]

On that day, Philip III ordered the Portuguese viceroy Cristobal de Moura to prepare for the arrival of Huseyn Ali bey with a letter sent from the hunting reserve in Castrocalbona.

On 16 October 1601, the embassy went to the settlement of Valsain, which is 14 kilometers away from Segovia. Arriving at El Escorial on 17 October, the embassy also toured the monastery. The Spanish court historian Fr. Jeronimo de Sepulveda noted that Huseyn Ali bey visited the monastery and stayed there for two days, and was treated well by the monks. Sepulveda emphasized that Huseyn Ali bey was witty and as proof cited when three Spanish women asked him, “Which one of us is the most beautiful?” the ambassador answered “decide among yourselves.” As noted by earlier observers, Sepulveda also considered the way Huseyn Ali bey ate food as animal-like:

He observed everything with great interest. We went to the inn one day when the priests of this house were eating, and they were eating like animals. The ambassador was a real man and represented his country well as an honorable man.[35]

The priest Sepulveda also testified that Huseyn Ali bey was a musician. According to him, Huseyn Ali bey asked for a lute at the end of the meal and played some tunes in tones very different from those used in Spain. Then he sang praises to the king, the monastery, and the hospitality shown to him.

Also interesting is that he requested 13 original architectural plans published in 1599 by the architect Juan de Herrera and wanted to take them to Iran because Huseyn Ali bey liked the Escorial Palace very much.[36] Huseyn Ali bey went to the cities of El Pardo, Madrid, Aranjuez and Toledo, according to the writings of both Sepulveda and Oruj bey. Luiz Cabrera de Córdoba mentions that Huseyn Ali bey went to Madrid to visit the 72-year-old Maria of Austria, the widow of Emperor Maximilian II.[37]

After leaving Toledo, the embassy reached the cities of Trujillo and Merida where they encountered a murder. Huseyn Ali bey rented a house for the night in Merida, and the embassy attracted great interest of the city’s population. The well-regarded Seyyed Amir al-Faqih, the mullah of the embassy was stabbed to death here. The killer escaped because it was nighttime and the corregidor[38] of Merida could not find the killer. Huseyn Ali bey was angry at the incident and wanted to return to Valladolid, but after learning that the king was still on a hunting trip, he decided to send an envoy to the palace after reaching Lisbon. According to Oruj bey, the mullah was buried according to the Shia tradition, and the townspeople who watched the funeral laughed at this.[39]

The embassy, moving towards Portugal, arrived in the city of Badajoz and was greeted by the corregidor Don Juan de Avalos, who gave them an official banquet. Oruj bey does not give any information about the road from Badajoz to Aldea Gallega or about when the embassy entered Lisbon. From the information provided by viceroy de Moura, the embassy entered Lisbon on 8 November 1601. Antonio de Escobar had refused the embassy citing his old age. Viceroy de Moura describes his meeting with Huseyn Ali bey as follows:

From the other side of the river, he sent word, so I sent an authorized envoy to him, and afterward, the galleys went and brought him to the lodging we had very well prepared for him and all his people, where he is being given all the good treatment and hospitality that Your Majesty has ordered; and he is served by honorable servants of Your Majesty. He and his servants were so pleased with the wines of this land that they indulged more than was advisable. And so, in the first few days, he was not in the best condition to negotiate. Afterward, he came to the palace, where I waited for him accompanied by the gentlemen I had with me, and I sent the captain of the guard to fetch him, who brought him with the same guard, giving him due respect. Upon arrival, he complained greatly to me about a servant who had been killed in Mérida and said that, because of this, and also to report something of importance to Your Majesty, he needed to send one of his servants to the court. I tried hard to dissuade him from this, offering him all the good offices with Your Majesty so that everything he wanted would be responded to well and promptly. It was of no use, and so about six or seven days ago, his servant left from here, accompanied by the Catalan canon who came with the ambassador, who had promised me that he would try to stay and not take the servant.[40]

The servant referred to here was Oruj bey Bayat.[41] This journey of Oruj bey would later lead to his conversion to Christianity.

Although Huseyn Ali bey got along well with everyone during the trip, it seems that he started behaving differently in Portugal. The viceroy especially did not like his behavior. In his report to the king, he stated the following:

Many gentlemen have seen him, and he is sociable with everyone, and to some of them, he has shown the dispatches from Your Majesty and has explained his embassy. When I found out, I ordered him to be reprimanded for it, and he promised to amend. He he has requested money from account of the eight thousand ducats to be given to him, and he wants half of it immediately. It will be given to him as Your Majesty has ordered; but I understand that he wants to spend it all on merchandise to take with him, including a large quantity of lances, swords, and arquebuses. I ordered him to be told that this cannot be done because our religion forbids it, and I do not know if Your Majesty could allow it (even if you wished). He is very displeased that not everything he wants is granted to him at the very moment he asks for it. […] He wants to be given all the tapestries with which the house is decorated and the silverware with which he is served. I ordered that he be told that these belong to the treasury of this kingdom, that they were ordered to be made by the kings to host ambassadors from great princes, and because they belong to the crown, they cannot be taken. He has accepted this. He seems to me a person who will cause trouble while he is here; but as it is to serve Your Majesty, we will bear it all with patience. May God protect Your Majesty as I desire and as Christendom needs. [42]

Another problem the Viceroy had with Huseyn Ali bey was that the latter was courting the wife of his Armenian translator Tommaso. As this was an unheard of complaint about Huseyn Ali bey, Carlos Alonso explains it this way: “Perhaps Huseyn Ali bey felt empowered to take certain ‘liberties’ as he saw himself nearing the end of his journey.”[43]

The viceroy’s letter was discussed in Valladolid on 1 December. The royal council decided that Huseyn Ali bey could not buy more than 4.000 ducats worth of weapons, and even if he did, Shah Abbas was an enemy of the Ottomans, so he was not subject to the “In Coena Domini” order. However, the viceroy was instructed not to give more than 4.000 ducats. The royal council instructed the viceroy to behave with restraint regarding the Armenian translator and his wife, and if necessary, to prevent him from going to Iran with the ambassador. According to the council, that translator could not be trusted.[44]

Meanwhile, ninety days had passed since Oruj bey had left for the capital. Huseyn Ali bey also asked about Oruj bey’s whereabouts in his letter to King Philip III on 24 December 1601:

It has been more than a month and a half since I sent Aorisvec[45] (sic), a Persian and my servant, to solicit the favors I requested from Your Majesty at that court, along with another memorial I sent from this city. I have learned that Your Majesty wishes him to remain in your service in these parts. This brings me as much joy as if I were serving my own king. And being so, I humbly request Your Majesty, if he [Oruj Bey] does not return with the dispatch, to send it to me as soon as possible, as my embarkation is approaching, and arrangements need to be made. […] As time is running out, I humbly request further favors at every moment, and, if possible, I humbly request Your Majesty to grant me five slaves who are in these galleys of Portugal under the command of the Marquis of Santa Cruz, and understanding that I am in Your Majesty’s favor, I dare to make such a request.[46]

Huseyn Ali bey’s request for five additional slaves in his letter can be explained by the fact that his embassy lost many servants along the journey. I will mention another possibility when talking about Oruj bey. The Marquis of Santa Cruz[47] was the chief admiral of Portugal and had control of the ships. But the frequent writing of letters and the late passing of royal assemblies delayed communication. The letter arrived at the palace the following year on 15 January 1602. During this time, Philip wrote another letter to his deputy on 28 December, strictly instructing him not to give any more money to Huseyn Ali bey. This even offended his viceroy; de Moura wrote a letter of protest and stated that he would do his part. In a letter dated 28 January 1602, he advised three ambassador candidates to be sent to the Safavids: Don Luis Pereira de la Cerda, Don Vasco Fernández Pimentel, and Don Gonçalo Vaz Coutinho.[48] The first two of them served for a long time in Goa, and the third was the captain of San Miguel Island. The viceroy mainly advised Don Pereira. In the letter, the viceroy complained about Huseyn Ali bey and also asked a reward for his steward Jorge de Mascarenas who was “tolerating” the ambassador.[49] The ambassador was expected to return to his country in mid-February.

Secretary of State Andrés de Prada,[50] delivered Huseyn Ali bey’s letter to the Duke of Lerma and reported that he was not aware of Oruj bey’s arrival.[51] In the reply of the king to the viceroy dated 22 February 1602, it was stated that the slaves should not be given to Huseyn Ali bey, and the ambassador most likely wanted to get money by selling them. However, he was asked to convey it diplomatically. It is interesting that Philip also wrote that he was not aware of the arrival of Oruj bey.[52] In a letter written on 16 March 1602, the king accepted the proposal of the viceroy as ambassador. The king wanted the viceroy to then hurry and join Huseyn Ali bey. But it was too late for: the viceroy noted that two days ago, Huseyn Ali bey had chosen a ship called San Roque,[53] had received the rest of the money, had been given a good cabin and a servant, but the ambassador had left with a bit of displeasure:

He expresses satisfaction with what has been done, and rightly so, although he is very distressed that almost all of his servants have left him due to his bad temperament and poverty, which he has displayed clearly here. Today, the Christian convert has left for the court, taking another with him who also wishes to convert. They have been entrusted to Francisco de San Juan, a footman of Your Majesty, who came with one of them by order of the Duke of Lerma, as he told me. I have given them all money for the journey.

With all this, this journey has come to an end. It has been a great deal of work for me and a significant expense for Your Majesty’s estate, but none of this can be avoided on such occasions.[54]

We learn from the writings of Oruj bey why the viceroy and the Duke of Lerma knew whereabouts of Oruj bey, while the king and the state secretary said they did not. According to his account, when he returned to Valladolid, he first looked for Aligulu bey Bayat and found him in the Jesuits’ house.[55] Oruj bey claimed that he came to Christianity after conversations with Aligulu bey and as a result of divine intervention. He wrote that he became officially a Christian at the persuasion of Alvaro de Carvajal, the king’s chief cleric. Later, Oruj bey kept the information secret in his meeting with the Duke of Lerma because he still wanted to return to Iran and his wife and child.[56] In my opinion, main reason why Oruj bey became a Christian was most likely not a divine awakening, but rather the influence of people who knew the Turkish language with whom he was constantly in contact. Even according to Oruj bey himself, Aligulu bey thought that he would live a more prosperous life in Spain than in his own country.

Oruj bey mentions in his memoirs that they left their place of residence wearing white clothes and entered the palace in a horse-drawn carriage together with de Carvajal. Oruj bey was baptized with Aligulu bey Bayat in the chapel of the palace, and his godfather was Philip III and his godmother Queen Margaret. Although Oruj bey did not mention the day of this event, it took place on 14 January 1601, according to the report of nuncio Ginnasi. At the end of the solemn ceremony, Aligulu bey was renamed “Don Felipe”[57] and Oruj bey was renamed “Don Juan.” Oruj bey received a new letter from the king and left again with Francisco de San Juan, his new translator.[58] Apparently, the latter was an Ottoman Turk who converted to Christianity.

Oruj bey later returned to Lisbon again and met Huseyn Ali bey for the last time. During the meeting, Oruj bey told Huseyn Ali bey that he wanted to return to the country by land rather than by sea, which most likely raised doubts in the ambassador. Oruj bey explained his choice by saying that he did not like the long journey, and said that he could return to Iran from Venice in 3-4 months in the guise of a Turkish merchant. According to Oruj bey, Huseyn Ali bey already knew about his and Aligulu bey’s conversion to Christianity. The viceroy, in a meeting with Oruj bey, advised him not to return to Iran. During the conversation, Oruj bey heard that Huseyn Ali bey and Hasan Ali bey, the fourth secretary of the embassy, were discussing arresting him after he returns to Iran. Oruj bey sent Francisco to inform the viceroy and soon incurred the wrath of the ambassador and reported that he would be killed if Francisco did not intervene.

Oruj bey later tells in his memoirs that before leaving, the ambassador tried to buy a Turkish prisoner from the Marquis of Santa Cruz’s ships and tried to have Oruj bey assassinated.[59] This information proves the authenticity of official correspondence in the Spanish palace. Perhaps Huseyn Ali bey already had doubts about Oruj bey becoming a Christian on 24 December. Huseyn Ali bey was able to buy at least one slave. According to Oruj bey, the viceroy’s admiral was warned about this plan, and the admiral came with 20 soldiers and arrested that slave again.

Oruj bey finally left the embassy and stayed in the room allocated to him by the viceroy. He never returned to his country after that. Oruj bey also convinced the third secretary Bunyad bey, to stay in Spain. During his stay, he met Nicola Clavel, a Venetian merchant in Lisbon who knew Turkish. Seeing a white dove during one of his discussions with Clavel, Bunyad bey suddenly agreed to become a Christian. As a result, Oruj bey and Bunyad bey left for Valladolid, this time for the baptism of Bunyad bey, without saying goodbye to the ambassador. Nicola Clavel—whose real name was Nicola Crivelli—would later continue to live in Spain, meeting the Safavid ambassador Tengiz bey Rumlu in 1611 and continuing to play an important role in Spanish-Safavid relations.[60]

It seems that Huseyn Ali bey left for Iran on 14 March 1602. The ship San Roque would most likely circle Africa, round the Cape of Good Hope, and go via the East African coast first to Goa and then to Hormuz. Huseyn Ali bey planned to leave Hormuz island for Isfahan and present his report to Shah Abbas. King Philipp III learned about Huseyn Ali bey’s departure only on 22 April 1602. In his letter written to Secretary of State de Prada on 29 June 1603, Viceroy de Moura stated that Huseyn Ali bey had arrived safely in Goa.[61] Considering that it took an average of 6 months for ships to reach Goa from Portugal at the time, San Roque probably arrived in November of that year. Although Antonio de Guvea—ambassador to the Safavid state in 1602-1613—stated in his memoirs in 1606 that he saw Huseyn Ali bey in Isfahan, unfortunately, the Safavid sources are silent about his fate.

The fate of Oruj bey, Aligulu bey and Bunyad bey

The Safavid secretaries who remained in Spain then led an interesting life. On 23 May 1602, in a decree written to state treasurer Pedro Mexía de Tovar, Philip III ordered a monthly stipend of 100 ducats for Oruj bey and the appointment of a priest to ensure his conversion.[62] Later, Bunyad bey, who entered the royal cortege that left for the El Escorial Monastery, was baptized there on 15 July 1602 with Philip III as godfather and the Duchess of Lerma as godmother. He received the name “Don Diego.” Fr. de Sepulveda also witnessed the ceremony.[63] The baptismal document of Bunyad bey was signed by Alvaro de Carvajal, written by priest Lucas de Alaejos, and witnessed by priests Miguel de Santa Maria and Moreno. It is now preserved in the parochial archives of El Escorial, in the second book of baptisms dating from 1594-1623.[64]

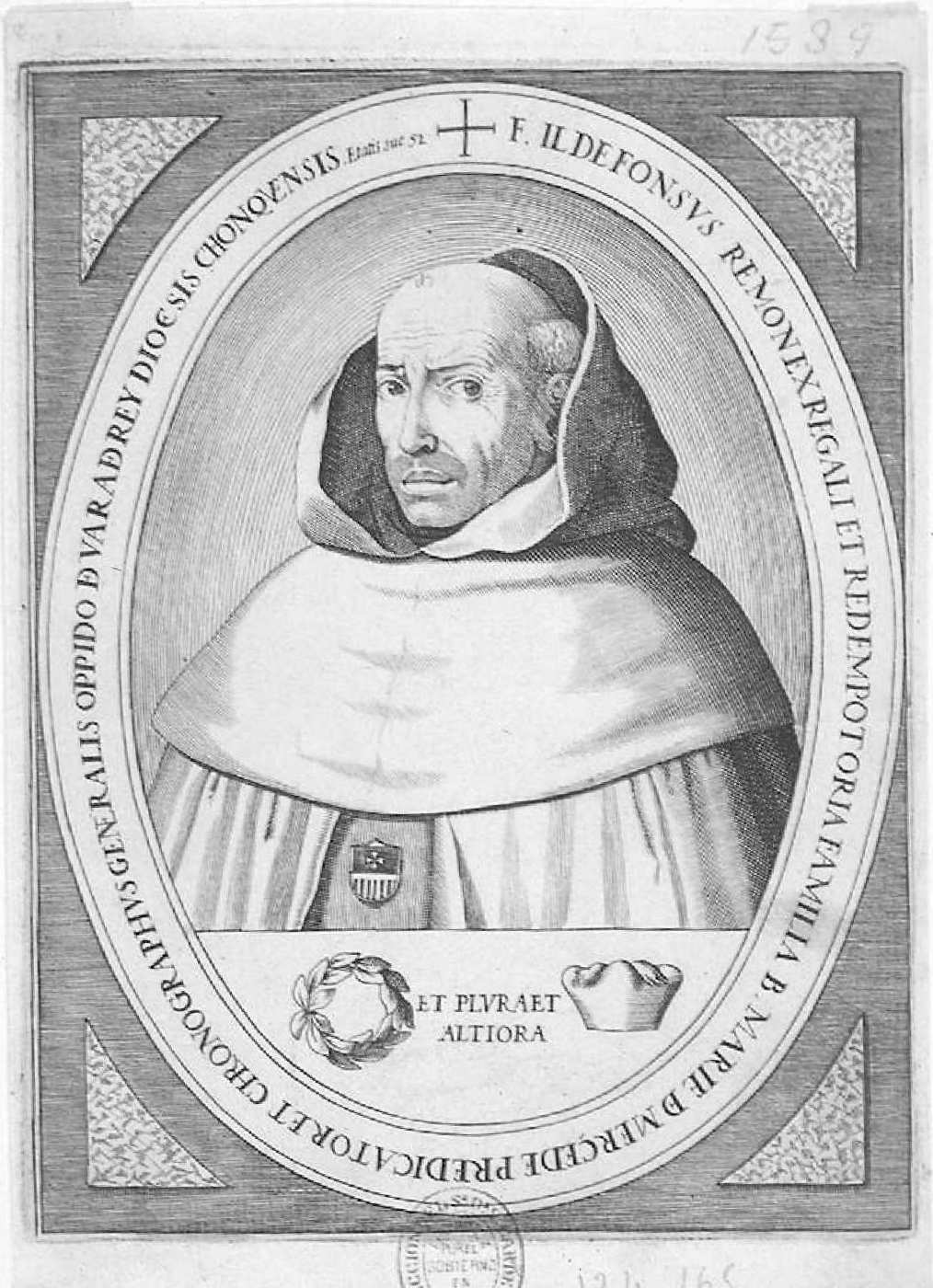

Oruj bey stops his Relaciones de Don Juan de Persia (The Information of Don Juan of Persia) at Bunyad bey’s conversion to Christianity. There are doubts that this book belongs entirely to Oruj bey. According to the Spanish literary historian Emilio Cotarello (1857-1936), an Iranian who had just become a Christian could not have become fluent in Castilian in order to write a book in such a short time. According to him, the original co-author of this book was actually Alonso Remón.[65] Alonso Remón (1561-1632) was a member of Augustinian order and a follower of de Carvajal. Francesco de Galarza (1548-1606), who approved the book for print, was the head of the Jesuit house where Aligulu bey was converted. On 20 October 1603, Galarza, the censor of Castille at this time,approved the book. It is thought that Alonso Remón actually wrote many parts of the book, such as that about Ignatius Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit order, the specific nuances of Christianity and Spanish geography that would be difficult for an Iranian who had just become a Christian to know.[66] However, in my opinion, the original was certainly written in Persian or Turkish. Because there is information about the Qizilbash tribes unknown to the Spaniards at that time, and at the end of the book there are translations of various Persian and Turkish words. He not only gives the translation of words such as “darugha,” (provincial head) “eshikaghasibashi,” (minister of ceremonies) “akhta” (eunuch), “zahrimar,” (snake poison) but also explains personal names such as “Genghis,” “Imam Reza,” “Khudabanda” and “Parikhan Khanim.” It also indicates the etymological source by placing the letters “P,” “T” and “A” in front of each word. A stands for Arabic, P stands for Safavid Turkish, and T stands for Ottoman Turkish. For example, the word “emir” is marked with P, and “qapichi” is marked with T. And the word “oymaq” has both P and T.[67]

One of the widely spread falsehood about Oruj bey is that he was supposedly killed in a street fight in 1605. For example, Atif Islamzade, PhD in Philology and an ANAS[68] employee, notes in an article that Oruj bey was a victim of conspiracy by his Spanish rivals.[69] Anar Turan, a PhD student of ANAS Institute of History, notes that “on 15 May 1605, he quarreled with the Safavid ambassador and killed him in a sword fight” without citing any source.[70] In her article, the head teacher of ASU, Jala Gambarli, notes that previous studies like these are mistaken in their description of Oruj bey’s death, but still does not provide information about the subsequent fate of Don Juan (Oruj bey):

Until recently, it was believed that Oruj bey was killed in 1605 in the city of Valladolid. This misconception spread after Pascual de Guyangos printed small excerpts from Pinheiro de Vega’s book “Fastiginia” in a Spanish magazine. Here he notes that on 15 May 1605, during a dispute between Don Juan and the Iranian ambassador, the ambassador killed Don Juan with a sword. But after “Fastiginia” was printed in full, it became clear that when Pinheiro de Veiga wrote about this incident, he did not mention the ambassador killing Don Juan, but Don Juan killing the ambassador.[71]

In fact, it was not an ambassador who was killed, but Cochacen (probably, Khoja Hasan), the secretary of ambassador Bastamgulu bey. He actually died on the trip to Spain.[72] Bastamgulu bey would be the next ambassador of Shah Abbas and would come to Spain with Diego de Miranda. Oruj bey and Bunyad bey were accused of murder and after spending a year and half in prison, they were able to get out after the confession of the real killer, another member of the embassy, who later took the name of Francesco de Persia as a Christian.[73] Francesco himself justified the murder, explaining that the secretary attacked him after he declared that he wanted to become a Christian. In other words, Oruj bey did not have a fantastical character like Elchin Huseynbeyli’s “The Thirteenth Apostle—the 141st Don Juan,” nor was he killed. Contrary to Jala Gambarli’s opinion, the main source of this disagreement goes back to the murder of the mullah in the Safavid embassy in Merida. De Veiga writes that the ambassador made a book listing the women he had slept with, defamed up to 130 Spanish women, and thus his murder was justified by the locals. However, de Veiga himself does not believe this and considers it a rumor.[74] Presumably, the story of the murder of the mullah of the Safavid embassy was later spread across the country and mixed with the murder of Khoja Hasan. De Veiga then recorded the rumor even though he did not believe it himself.

Aligulu bey’s fate

In any case, neither Oruj bey nor his friends were killed. After a while, these Iranians, who decided to marry after a while, had to apply for royal permission. The marital status of a formerly Muslim and married person after converting to Christianity was a situation that had not yet been explored by the Church. On 29 November 1602, nuncio Ginnasi sent the request to Cardinal Aldobrandini about the desire of Aligulu bey and Oruj bey to get married.[75] Referring to the decretal of Pope Innocent III (1161-1216) called De Divortiis,[76] Ginnasi asked for information on whether it would be possible to fulfill this wish. The response to the reading of the letter was sent very late, on 14 January 1603.[77] But a decision could not be made. Ginnasi sent his new letter on 14 June 1603, at de Carvajal’s insistence.[78] After thinking for a long time, the Pope decided to summon the spouses of Oruj and Aligulu in Iran in accordance with church law. Since this would not be practically possible, King Philip III himself intervened this time and asked for permission for the new Christians. In this letter, it was written that Aligulu bey personally went to Rome.[79]

Finally, after long discussions, permission was granted only in 1604. But Aligulu bey had no money left and asked the king for help.[80] However, due to his imprisonment for murder, the marriage was postponed for a while. Aligulu bey was able to get married in Valladolid only on 25 January 1606, after he was acquitted of the criminal case. Aligulu bey married Luisa from Valladolid in the church of San Pedro and was presented as a person of Turkic origin in the marriage certificate.[81] But the couple did not live in this city and moved to Madrid. Soon a girl was born. Aligulu bey died on 12 June 1614.[82] In his will dated 18 May 1614, he said that he wanted to be buried in the Church of St. Martin in Madrid, and noted that Oruj bey owed him 200 reales and Bunyad bey 14 reales. One of the people he borrowed from was Francesco de Gurmendi, the king’s official orientalist and translator. Aligulu bey entrusted the execution of his will to his wife Luisa and Oruj bey. He most likely fell ill and knew he was going to die. It is interesting that among the things left by Aligulu bey after his death were his portrait, his wife’s portrait and a portrait of an Iranian woman.[83]

Oruj bey

On 16 May 1605, Oruj bey first took refuge in the French embassy for the murder of Khoja Hasan,[84] but then he was expelled from there and imprisoned for a year and half. Although he was released, he was not fully acquitted and was forced to serve in Flanders. At the same time as Aligulu bey, in 1606, he married a woman named Maria Villa(r)te from Medina del Pomar, Castille. The following year, a daughter was born to couple, whom they named Juana Bernarda.[85] On 13 February 1607, Oruj bey complained that he did not have the financial means to go to Flanders with Bunyad bey.[86] On 13 March 1607, Oruj bey moved to Madrid with the king[87] and received from the king’s secretary the amount due to him according to the decree of Philip III.[88] Having regained economic freedom, Oruj bey went into business and even hired a servant named Alonso Seoane Salgado from the village of San Juan de Crespo in Galicia. However, his luck did not last long, and on 13 January 1609, he appealed to the king again, saying that he was in debt, and the creditors were even taking his furniture for auction.[89] The king accepted this request for additional help. Oruj bey returned to a good financial situation: In his letter to the king dated 21 January 1611, he said that he had freed his servant and asked the king to find him a good job.[90] The king accepted this request on 7 February.

In March 1611, Oruj bey again had a chance to participate in the Safavid embassy mission. He was offered to accompany Tengiz bey Rumlu to Rome as his translator. Although Oruj bey accepted the offer, he was unable to do so because of Tengiz bey’s illness. Despite such problems, Oruj bey’s family affairs were going well. His daughter grew up healthy, and on 11 April 1612, he gifted his wife 1.600 real worth of jewelry: a gold ring with 9 diamonds, ring with a ruby and a ring with an emerald.[91] However, in 1615, another problem struck him. Oruj bey gave a Cristobal Hernandez power of attorney, and the latter then took a loan from the court in Oruj bey’s name, guaranteeing the expenses from royal pension for January and February 1616. Oruj bey, already in debt for 1.500 reals, went to the notary to say that he did not give Cristobal Hernandez the right to take a loan in his name. He did this with the testimony of former servant Alonso Seoane and other Spaniards.

Oruj bey had a wide social circle in Spain. In addition to Aligulu and Bunyad bey, he was friends with the king’s translator, Francesco de Gurmendi. He wrote a sonnet for the book Physical and Moral Doctrine of Rulers[92] published by him in 1615. His other friends were people like Maximiliano de Céspedes, Agustín de Texada,[93] Alonso de Ledesma,[94] Segovia poetess Ana de Espinosa y Ledesma,[95] Agustin de Viruega, a compatriot of Miguel de Cervantes, who wrote poems for his book.

On 7 February 1616, Oruj bey appealed to the king again and asked him to stop the activity of the priest appointed by the king in 1602 to make sure that he did not leave the religion. In his opinion, knowing Spain for a long time, getting married here, having an 8-year-old child and being in debt were reasons enough not to fund this priest anymore.[96] The reply that came two weeks later stated that this request was accepted, and even that priest’s activity should have been stopped a long time ago. According to the royal council, Oruj bey was already a Spaniard.

In the third quarter of 1616, Oruj bey most likely lost his wife and was worried about his daughter’s future. On 5 November 1616, Oruj bey wrote a petition to the king, reminding that the king had given Aligulu’s daughter 30 ducats for expenses, and asked for his daughter to be given 100 ducats instead of himself. This request was also accepted.[97] On 12 June 1621, the petition written by Oruj bey’s daughter Juana Bernarda stated that she was already an orphan, and that she was a nun in the Pinto convent[98] in Madrid. Unfortunately, we do not know the date of Oruj bey’s death and the place he was buried.

Bunyad bey

Bunyad bey lived a more turbulent life after his release from prison. On 20 January 1609, he was seriously injured in a duel with his friend, the famous writer Alonso de Salas (1581-1635).[99] In the court case, Bunyad bey was referred to as “Don Diego de Persia” and was described as a 25-year-old warrior. [100] Bunyad bey, who lived on Calle del Príncipe, suffered severe wounds to his face and chest. In 1614, Bunyad bey, who became a knight, fought against the Ottoman army in Larash, Morocco, which was captured by the Spanish. Bunyad bey, fought in the Mahdiyya fortress of Morocco under the leadership of Luiz Fajardo on 1 August 1614. He began serving in the palace in 1621. Although he wanted to apply as a knight of the Order of Santiago in April 1622, discussions about his candidacy dragged on because there was no serious information about his ancestors. Bunyad bey claimed to be a descendant of the “Xamen Dukes of Iran.” Baltazar de Zúñiga, the king’s new favorite and adviser on foreign affairs, wrote a petition defending him, but the head of the Council of Orders, the Marquis of Caracena,[101] rejected the application.[102] De Zúñiga’s death in October of the same year closed the way for Bunyad bey. Bunyad bey instead became one of the king’s gentleman-in-waiting in 1628 and applied to join the Order of Santiago again the following year. This time he was rejected by Juan de Villela (1563-1630), who worked in the state secretariat, and Pedro de Zúñiga (1560-1560), the former ambassador of Spain to England and one of the commanders of the Order of Santiago. [103]

On 21 July 1631, Bunyad bey ransomed the famous Flemish artist Juan de la Corte (1585-1660), who was imprisoned for debt, and asked him to paint for him three days a week in exchange for the 568 reales he paid.[104] Bunyad bey joined the military at the start of the French-Spanish war in 1636.[105] No further information about him has been found.

The result

Although the Great European Embassy sent by Shah Abbas in 1599 lasted an unexpected three years, it changed the world political scene to a significant extent. The European powers became more emboldened against the Ottomans and started sending more ambassadors to states like the Safavids and Russia to explore new trade routes. Shah Abbas’s new embassies created positive opinions about Iran in the West, but they did not bring serious results. Losing his motivation over time, Shah Abbas established relations with the new king of England, James I, with the help of the Shirley brothers and captured Hormuz in 1622, which had been under Portuguese rule since the reign of Shah Ismail. This, in turn, would result in a chain reaction of Portuguese separatists revolting to free themselves from Spanish rule and the re-establishment of Portugal as an independent kingdom.[106]

References and notes

[1]For earlier articles, see: Javid Agha, “Shah Abbas’s European Spies – First Contacts,” Baku Research Institute , January 21, 2024, https://bakuresearchinstitute.org/sah-abbasin-avropa-casuslari/ ; Javid Agha, “Shah Abbas’s European Spies – Great European Embassy,” Baku Research Institute , February 22, 2024 https://bakuresearchinstitute.org/sah-abbasin-avropa-casuslari-boyuk-avropa-sefirliyi/ ; Javid Agha, “Shah Abbas’ European Spies – Secret Embassy,” Baku Research Institute , March 15, 2024 https://bakuresearchinstitute.org/sah-abbasin-avropa-casuslari-gizli-sefrilik/ ; Javid Agha, “Shah Abbas’s European Spies – The Grand European Embassy (Part II),” Baku Research Institute , April 14, 2024 https://bakuresearchinstitute.org/sah-abbasin-avropa-casuslari-boyuk-avropa-sefirliyi-2/ ; Javid Agha, “Shah Abbas’ European Spies – Polish Embassy” Baku Research Institute , May 25, 2024 https://bakuresearchinstitute.org/sah-abbasin-avropa-casuslari-polsa-sefirliyi , Javid Agha, “Shah Abbas’ European Spies – Rome Embassy” Baku Research Institute , June 28, 2024 https://bakuresearchinstitute.org/sah-abbasin-avropa-casuslari-roma-sefirliyi/ , Javid Agha, “European spies of Shah Abbas – Spanish Embassy and the transition to Christianity” Baku Research Institute , June 11, 2024

[2]Antoine de Silly (1540-1609) – Governor of Anjou and Count of La Rochepeau

[3]Vatican Archives, Spagna, vol. 54, p. 274r-v

[4]Pierre Paul Laffleur de Kermaingant, Lettres de Henri IV au comte de La Rochepot: ambassadeur en Espagne (1600-1601) , Paris, 1889, p. 106

[5] Francisco Gómez de Sandoval (1553-1625) – favorite of King Philip III, prime minister of the kingdom

[6]G. Le Strange, Don Juan of Persia, p. 290

[7] Fernando Niño de Guevara (1541-1609) – Archbishop of Seville and Chief Inquisitor of Spain

[8] Luis Jerónimo Fernández de Cabrera Bobadilla Cerda y Mendoza (1589-1647) – viceroy of Peru in 1629-1639.

[9] Juan Fernández de Velasco (1550–1613) –Governor of Milan 1592–1600 and 1610–1612

[10] Juan de Idiáquez y Olazábal (1540-1614) – Spanish Secretary of State, former ambassador to Genoa and Venice, and adviser to Philip II

[11] Antonio Álvarez de Toledo y Beaumont (1568-1639) – Viceroy of Naples

[12]Simancas State Archives (hereafter AGS), EST, document 463

[13]AGS, EST, document 187

[14]Carlos Alonso, Embajadores de Persia en las cortes de Praga, Roma y Valladolid (1600-1601): Anthologica Annua 36 (1989) p. 138

[15] Margaret of Austria (1584-1611) was the cousin of Anne of Austria, the mother of King Philip III. Anne of Austria herself was the niece of Philip II, from a consanguineous marriage. Due to these extensive consanguineous marriages, the line of the Habsburgs of Spain went extinct with the grandson of Philip II, Charles II.

[16]Luis Cabrera de Cordoba , Relaciones de las cosas succedidas en la córte de España, desde 1599 hasta 1614 , Madrid, 1857, p. 121

[17] Girolamo da Sommaia (1573-1635), Italian writer, explorer and historian.

[18] Original title of the manuscript: Rime di vari autori raccolte da Girolamo da Sommaia [Rhymes of various authors collected by Girolamo da Sommaia].

[19] Oruj bey’s song was recorded as “Love has taken me captive” (Tiéneme cautivo amor).

[20] Francesco de Benetictis, Tra letteratura di viaggio e memoria nella Valladolid del 1601, Letteratura della memoria , volume 1, Salamanca, 2004, p. 85-98

[21] Luis Gil, Apuntamientos para una biografía de don Juan de Persia. Boletín de la Real Academia Española , 2019, p. 617-632.

[22] Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc (1580-1637), French astronomer, antiquities collector and explorer.

[23] Marine Mersenne (1588-1648), French mathematician, musician and priest.

[24]See Cornelis de Waard et al, ‘ Correspondance du P. Marin Mersenne, Religieux Minime ‘, vol. 3, Paris, 1969, letter 283, p. 497–505. Quote: “…et ay veu moy mesmes l’Ambassadeur de Perse qui vint trouver le pape Clement à Rome l’an 1601, qui sonnoit de la guitarre tres volontiers et assez joliment.”

[25]Luis Cabrera de Córdoba , Relaciones , p. 119

[26]Paola Volpini, From Salamanca to Florence – The Collection of Books and Manuscripts of Girolamo da Sommaia (Early 17th Century), Paper Heritage in Italy, France, Spain and Beyond (16th to 19th Centuries) , Routledge, 2023, p. 118.

[27]Vatican Archives, Fondo Borghese, III, p. 130-B. page 144r. (Letter from Pietro Camerino, Secretary of the Apostolic Collectory in Spain, to Cardinal Aldobrandini: Valladolid, September 17, 1601)

[28]Vatican Archives, Confalonieri, vol. 22, p. 323r and 325v, Capitolo di lettera scritta da Vagliadolit del canonico Francesco Guasch alli 11 di Settembre 1601 [Contents of the letter of Canon Francesco Guasch from Valladolid dated 11 September 1601]

[29]Vatican Archives, Spagna, vol. 54, p. 344 v. Del nuncio en Espana D. Ginnasi a la secretaria de estado de Clemente VIII: Valladolid, 16 de octubre de 1601 [From the Spanish nuncio D. Ginnasi to the secretary of state of Clement VIII, Valladolid, October 16, 1601]. Quote: “Se dice que ha llevado consigo dos mujeres españolas de éstas. Si es así, no sé cómo han podido permitírselo.”

[30] Diego de Urrea (1559-1616) or Murad Agha, born in Naples, was captured by the Ottoman army at the age of 5-6, raised as a Muslim and given the name Murad. At the age of 30, he was captured by the Spanish army and converted to Christianity. Later, he worked as an Arabic, Turkish, Tatar and Persian translator for the Spanish court.

[31] Nuestra Señora de la Fuencisla

[32] Alcázar de Segovia – a Spanish fortress built on top of a Muslim castle

[33] Real Casa de la Moneda – It was one of the 6 main mints in Castile.

[34] Diego de Colmenares, Historia de la insigne Ciudad de Segovia y compendio de las historias de Castilla , vol. 3, Segovia, 1847, p. 261.

[35] Jerónimo de Sepúlveda, Historia de varios sucesos del reino de Felipe III, La Cuidad de Dios 128, 1922, p. 341-345

[36] Juan de Herrera (1530-1597) – Spanish architect, mathematician and geometrician.

[37] Luis Cabrera de Córdoba , Relaciones , p. 122

[38] Corregidor – A city executive who also served as the head of Spain’s law enforcement.

[39] G. Le Strange, Don Juan of Persia, p. 298

[40] AGS, EST, document 186 – Del virrey de Portugal D. Cristobal de Moura, marques de Castel Rodrigo, a Felipe III; Lisboa, 16 de noviembre de 1601 [Viceroy of Portugal, Marquis of Castel Rodrigo D. Cristóbal de Moura to Philip III; Lisbon, November 16, 1601]

[41]G. Le Strange, Don Juan of Persia, p. 299

[42]In the bull “In Coena Domini” written by Pope Urban V, it was forbidden to sell weapons to Muslims.

[43]Carlos Alonso, Embajadores , p. 154

[44]AGS, EST, document 618.

[45] Oruj bey Bayat is meant.

[46]AGS, EST, document 188 : De Husein Ali Beg to Felipe III: Lisboa, 24 de diciembre de 1601: original escrita en espanol defectuosamente por alguien que no entendía lo que escribia [From Husein Ali Beg to Philip III: Lisbon, December 24, 1601: original written in defective Spanish by someone who did not understand what they were writing]

[47] Álvaro II de Bazán (1571-1646) – Admiral in charge of the Kingdom of Portugal and the coast of North Africa. His father, Álvaro de Bazan (1526-1588), was also a famous admiral and one of the heroes of the Lepanto War against the Ottomans.

[48] AGS, EST, document 188: Carta de D. Cristóbal de Moura, virrey de Portugal, a Felipe III. Lisboa, 28 de enero de 1602 [From Don Cristóbal de Moura, Viceroy of Portugal, to Philip III. Lisbon, 28 January 1602]

[49] Jorge de Mascarenhas (1579-1652) was promoted and became the first viceroy of Brazil in 1640.

[50] Andrés de Prada y Gómez de Santalla (1545-1611)

[51]AGS, EST, document 188: Del secretario Andres de Prada al duque de Lerma: Valladolid, 31 de enero de 1602 [ Secretary Andre de Prada to the Duke of Lerma . Valladolid, January 31, 1602 ]

[52]AGS, EST, document 191

[53] A 600-ton galleon belonging to the Portuguese Navy. In 1606, while leaving Havana for Spain, it was caught in a storm and sank near the Bahamas. The captain of the ship was Ruy Lopez.

[54] AGS, EST, document 188: Carta de D. Cristobal de Moura, rirrey de Portugal a Felipe III: Lisboa, 14 de marzo de 1602 [From Don Cristobal de Moura, viceroy of Portugal, to Philip III. Lisbon, 14 March 1602]

[55] Colegio de San Ambrosio de Valladolid – operated in 1543-1767.

[56] G. Le Strange, Don Juan of Persia, p. 300-301

[57] Most likely, in honor of the king.

[58] G. Le Strange, Don Juan of Persia, p. 303

[59]G. Le Strange, Don Juan of Persia, p. 305

[60]AGS, EST, document 2642.

[61]AGS, EST, document 194

[62]AGS, EST, document 1815

[63]Sepulveda mistakenly introduces him as the ambassador’s nephew, confusing him with Aligulu Bey. See Sepúlveda, Historia de varios sucesos , p. 98

[64]Carlos Alonso, Embajadores , p. 154

[65]Emilio Cotarelo, Obras de Alonso Jerónimo de Salas Barbadillo. volume I. Corrección de vices y La sabia Flora, malsabidilla, Madrid, Tipografía de la Revista de Archivos, 1907. Pg. xxxii

[66]Enrique de Jesús García Hernán, Persian Knights in Spain: Embassies and conversion processes, The Spanish Monarchy and Safavid Persia in the Early Modern Period politics, war and religion, Colección Historia de España y su Proyección Internacional , 2006. p. 63-97

[67]For more, see: Relaciones de Don Juan de Persia, 1604, page 201 https://www.google.az/books/edition/Relaciones_de_Don_Juan_de_Persia/AHPsKQkdIRMC?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA200-IA1&printsec=frontcover

[68] Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences

[69]Atif Islamzade, The Lie of Four Hundred Years – Oruj Bey Bayat aka Don Juan, mia.az 03.08.2017 ( https://mia.az/w256701/dord-yuz-ilin-yalanidon-juan-legebli-oruj-be y -bayat )

[70]Anar Turan, a famous Azerbaijani nicknamed Don Juan… or a friend of Miguel de Cervantes, Xalq Gazeti 22.04.2012 ( http://old.xalqqazeti.com/az/news/social/21284 )

[71]Jala Gambarli, Oruj Bey Bayat, or Persian Don Juan?, Scientific Work , volume 20, issue 4, 2010

[72]AGS, EST, document 2748.

[73]AGS, Cámara de Castilla (hereafter CC), document 911, p. 110. 22 January 1607

[74]Tomé Pinheiro da Veiga, Fastiginia o Fastos geniales , Valladolid, 1916, p. 33-34

[75]Vatican Archives, Spagna, vol. 55, p. 427 r

[76]These decrees were later collected by Pope Gregory IX (1145-1241) in the book Decretalis. For the original Latin text of the judgment, see: http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/gregdecretals4.html

[77]Vatican Archives, Spagna, vol. 331, p. 18r-v

[78]Vatican Archives, Spagna, vol. 58, p. 168r (copy); Borghese, III, vol. 94 A.1, clause. 410 (original).

[79]Madrid, Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Santa Sede collection, vol. 54, p. 60r-v (copy): Carta de Felipe II al duque de Sessa, embajador espanol en Roma. El Pardo, 24 noviembre 1603 [Letter of Philip III to the Duke of Sessa, Spanish Ambassador in Rome, El Pardo, 24 November 1603]

[80]AGS, Consejo de Hacienda, document 449, 6–15 December 1604

[81]Original names: Father – Juan de Quirós , mother – Doña María de Arce, wife – Doña Luisa de Quirós; Dr. Miguel Gómez. Archival document: San Pedro Prixod Archives, Valladolid, Book of Marriages 1603-1655, p. 6

[82]AGS, EST, document 2748

[83]García Hernán, Persian Knights in Spain, p. 96-97

[84]AGS, EST, vol. 2637, p. 13, 116, 117 and 150

[85]Historical Archive of the Madrid Protocols (hereafter AHPM), documents 4429 and 5322

[86]AGS, CC, document. 912, p. 68

[87]Original name: García Mazo de la Vega (1550-1620)

[88]AHPM, vol 1854, p. 174 rv

[89]AGS, CC, document. 966, p. 24

[90]AGS, CC, document. 981, p. 106.

[91]Beatriz Alonso Acero, “Being so thoroughly Spanish, the Persians” – conversion and integration during the monarchy of Philip III, The Spanish monarchy and Safavid Persia in the early modern period: politics, war and religion, 2016, ISBN 978-84-7274 -318-2, p. 119

[92] La Doctrina Physica y Moral de Príncipes

[93] Agustín de Tejada y Páez (1567-1635)

[94]Alonso de Ledesma (1562-1623) – the founder of the conceptual movement.

[95]Angel Revilla, Notas para la historia de la poesía Segoviana , 1956, vol. 8, p. 20

[96]AGS, EST, document 1824, unpaged

[97]AGS, EST, document 1826, unpaged

[98]Iglesia del convento de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción (Pinto)

[99]AGS, EST document 1649, p. 98

[100]Francisco Rafael de Uhagón, Dos novelas de Alonso Jerónimo de Salas Barbadillo, Madrid, 1894, p. xiii

[101] Luis Carrillo de Toledo (1564-1626)

[102]Salamanca University Library, manuscript 1925, document 14, p. 29-31

[103]AGS. EST. document 2756. rescript, February 1, 1629

[104]AHPM, protocol 6080, p. 328r-329v

[105]Madrid Palace Archives, case 827, specimen 16 – Don Diego de Persia

[106]Graça Almeida Borges, El Consejo de Estado y la questión de Ormuz, 1600-1625: políticas transnacionales e impactos locales. Revista de Historia Jerónimo Zurita, 2015, Evora ; p. 21–54.